The year is 1630. The sailing ship Eendracht anchors at Fort Oranje far up the Hudson River. Annika and Rolf Jansson from swedish town Marstrand) (then Norway) step ashore with their two daughters. In the company are Annika’s sister and mother, also from Marstrand.

The other passengers are bachelors; six Dutchmen and Rolf’s two farmhands from Flekkeröy – the island outside Kristiansand where Annika grew up. By all accounts, Rolf – or Roeloff Jansen van Masterlandt as he now calls himself – is Swedens first settler in America, seen to the borders today. Kalmar Nyckel first sailed up the Delaware River eight years later.

After many hardships, the family had a good life. Rolf’s mother-in-law Tryn became New Amsterdam’s (and thus New York’s) first nurse and midwife. After three marriages, his sister-in-law Maria could count herself as perhaps the richest in the colony. Sara married a New Amsterdam surgeon. The strangest class trip was probably made by Annika, or Anneke, which is the Dutch name. As a priest’s wife, she became second in rank after the governor’s wife. The heirs have sued over her land, which is worth billions in the middle of New York’s financial district.

The Sodom and Gomorrah

We would like to see Rolf as a Swede, but the peace of Roskilde was not concluded until 1658. He was born in 1602 in Marstrand, like his father Jan four decades earlier, to parents who had immigrated from Holland. The Frisians knew how to fish on the North Sea banks and they followed the herring to Bohuslän in the years after 1556. We do not know whether Rolf in Marstrand spoke Norwegian, Dutch or Frisian primarily. Nationality was not so important then. More important was to be able to practice the true Reformed doctrine. In their homeland, the Dutch, led by William of Orange, wanted to throw off the Spanish yoke. It has been claimed that Anneke’s surname was Webber and she was the illegitimate daughter of this prince, but this is a romanticized legend.

Let’s take a look at Marstrand in 1585, the year that Tryn saw the light of day there. Hundreds of fishing boats from all over the north crowd the fjords. Marstrand is Europe’s herring trade center. After Copenhagen, Marstrand is said to be the richest city in Denmark and is undoubtedly King Frederick’s main source of income. The docks are bustling with life. Many from upcountry have flocked to clean fish. The ships are loaded with barrels of timber and German salt. Others are loaded with barrels of herring because there is great demand on the continent, especially around Lent. This year, the Öresund Customs expects more than 100 ships to pass through Marstrand with cargo.

(Addition: Peder Brems from Toftenäs on Tjörn was at this time mayor of Marstrand, and then lived at Bremsegården on Klåverön south of Marstrand.).

German merchants came here as early as the Hanseatic period. They have now faced competition from the Dutch and several other nationalities, especially since King Frederick banned foreigners from trading fish outside Marstrand.

Many languages are spoken in the alleys up to St. Mary’s Church, especially notorious are the deposed Scots. Mayor Torger Torgersson and his ten councillors, the village bailiff and a syndicus are busy with whores and fights in the taverns. God’s punishment will befall the most sinful city in the North, say many, and their prayers are answered with great success. The city burns down in 1586 and perhaps worst of all, the herring disappears in 1589 as quickly as it arrived.

Perhaps it was then that Tryn’s parents moved to Flekkeröy, a fortified town not unlike Marstrand. At eighteen years old, Tryn gave birth to Maria (Marritje) and a couple of years later Annika was born. Did her husband Jonas make a living from the timber trade? Large quantities of timber were exported from Southern Norway, which the Dutch needed for all their new houses and boats.

The alley in Amsterdam

Rolf became an orphan at an early age and went to sea. At the age of eighteen he appears in the alley St. Tunis in Amsterdam, where the widow Tryn and her two daughters have also moved. Love arises between Rolf and Annika and they get married on a spring day in 1623 in the New Reformed Church. Tryn is a witness when Rolf signs the marriage certificate with an R and Annika with a +. From now on we will call her Anneke, because it is under that name (and also Annetje) that she is known.

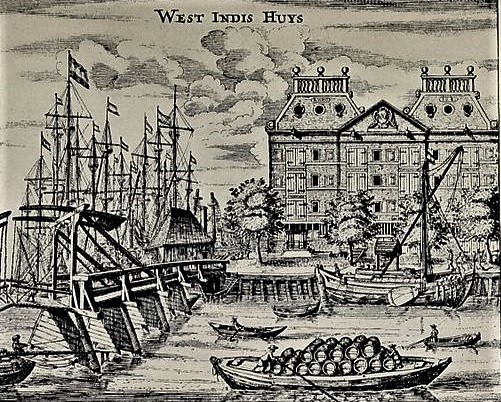

In these poor quarters live Norwegian lumbermen and Danes who dig canals, of whom there are more than in Venice. Swedish sailors who escaped from the king’s fleet are waiting for a new hire. The Saxons have found refuge from the war. The Pilgrim Fathers lived here for a while before continuing their journey on the Mayflower. A few Jews pass by on their way to the diamond mill. In the weavers’ quarters the French tongue rings out. The Inquisition has hunted Huguenots and Walloons here; some have already gone to America. As general manager of the West-Indische Compagnie, the Walloon Peter Minuit has bought Manhattan from the Indians for 60 guilders – and he will later serve Queen Christina and found New Sweden in Delaware.

The portrait painters are busy painting all the newly rich who, during Amsterdam’s golden years, make a good living from the East India trade. One is the diamond merchant Kiliaen Van Rensselaer, who is now a director of the West India Company. Van Rensselaer advertises for people who want to settle in the large area of land he has acquired on the Hudson River. Few Dutch people listen to the appeals; why scalp in the wilderness when you can live well in the land that flows with milk and honey? Instead, poor immigrants take the bait; like Anneke and Rolf, life in St. Tunis alley is scarce. Shortly before departure, the eldest daughter Lijntje dies and she is buried in the poor cemetery.

The journey

One March day in 1630, the small family finds themselves on the Frisian island of Texel where they embark on the Eendracht . The question is what Anneke fears most: the hardships on board, the storms, or being taken as a slave by pirates in the West Indies.

But life is also adventurous in Marstrand. Sara’s eyes widen when Grandma Tryn tells her horror stories during the trip. Like when the Scottish knights killed the priest and his servants in Solberga in the winter of 1586; all except a maid, who hid behind the kitchen wall. When the maid later became a fish cleaner in Marstrand, she heard one Scotsman say to the other in the tavern ”drink brother, Mr. Arne’s money is still enough”. A mountain in Solberga is still called Stegelberget. There the criminals were smoked, then chased around a stake with their intestines nailed to it – to finally be lifted onto a pyre with red-hot tongs.

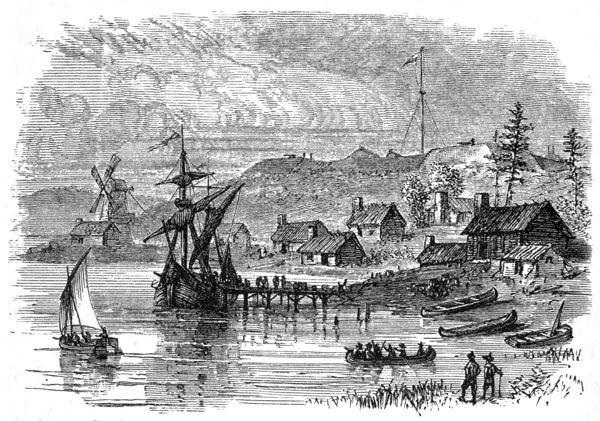

Thankfully, the two-month Atlantic voyage was uneventful. On May 24, the Eendracht approached Manhattan and the Jansson family was able to stretch their legs in New Amsterdam, at that time only about ten houses below a redoubt. The journey continued about twenty miles up the Hudson River to Fort Oranje at the rapids where Henry Hudson had to turn back in his search for a shipping route to India in 1609.

Exploitation took off when the West India Company gained a monopoly on the fur trade and large areas of land were distributed to feudal patrons, where the tenants were practically serfs. The patron was his own court and decided almost everything in his fiefdom. The most successful was Kiliaen van Rensselaer with Rensselaerwyck , where Rolf moved as one of the first tenants.

Playing with the Mohicans

Let us use historical fragments and imagination to glimpse life at Laets Burg, which means the farm in the pine forest. The thatched house is built of bricks, which the ships brought with them as ballast. Other houses are built of planks sawn in the windmill on the hill, where the farmhand Jacob Goyverttsen usually helps. At the stable, Rolf harnesses one of the four horses. In the field below, Claes Claesz threshes the wheat. The cows and a dozen or so sheep graze at the bend in the river, which is still called Roelof Jansen Kill today.

Some of the Indians’ children have come here and are playing with Sara and Trijntje. Sara learns the Mohawk language so well that as an adult she can work as an Indian interpreter. The Indians are now as pious as lambs, it is said. Skins are exchanged for tools, weapons, brandy and wampoons, that is, coins made from mussel shells.

But when the hunting fails, famine and disease threaten. Patron accuses Tryn of wastefulness, perhaps because she was too generous to the natives.

The farm’s twenty morgens (four hectares) may seem small, but Rolf earns $75 a year as a supervisor. Although Rolf probably didn’t have time to fulfill his duties as an alderman in the magistrate’s office.

There are better places than Marstrand if you want to learn agriculture. The patron grumbled, as when Rolf did not have time to sow the autumn seed. The Jansson family left Laets Burg in 1634 before the contract expired, with debts to the patron for seed and livestock. Van Rensselaer himself was in Holland and managed the patronage remotely.

More tenants who could not stand the bailiff’s rule left. Some farmers, perhaps including Rolf, defied the ban and traded in furs. Some moved to nearby Beverwyck (today Albany, the capital of the state of New York).

Rolf took a job as a sailor with the West India Company to go to Brazil. In 1636, the company gave him the right to farm 62 acres on the North River in Manhattan. That much tobacco was probably not grown on the meager hills and marshes on the North River. The question is whether the house was finished when Rolf died in 1637. Anneke, in addition to the two oldest children, had to support two small children alone and another was on the way. The Indians showed their battle axes and it was far to the neighbors. Therefore, Anneke rented out the farm and moved to New Amsterdam.

The priestess

Anneke complains of her distress to the parish priest, Domine Everardus Bogardus . Love arose and they married in 1638. The learned Bogardus had studied in Leyden, she could not even write. Everardus was orphaned early and was placed in an orphanage to become a tailor, but thanks to his talent he came to a Latin school. An illness made him deaf, mute and almost blind – until the defects disappeared during the singing of hymns at high mass. In gratitude, Evardus dedicated his life to God, first as a spiritual servant in Africa and after 1634 as a domino in New Amsterdam.

The marriage appears to have been a happy one. The energetic Anneke was able to take care of the practicalities for a life of pleasure who often got into trouble. Things were not made worse by Evardus being able to merge his farm, which bordered Anneke’s in Manhattan. He also owned land on Long Island, but his interests were probably not worldly.

There was a lot of gossip about the couple, who were considered to be mismatched. In a defamatory letter, the neighbor Grietje Reiners accused the newlywed Anneke of indecently lifting her skirt above her ankles in the mud outside the blacksmith’s shop. Grietje would not have done that, because Everadus put Grietje’s husband, the mulatto Anthony Jansen, in prison for unpaid church tax. The skirt case ended up in court, which was not the only time the two families had a dispute in court.

Grietje’s reputation was not the best. She was considered Manhattan’s first whore with several illegitimate children, you could tell by her fair skin. Tall Anthony was called the Turk because his Dutch father (who was a pirate admiral to the Sultan and in a raid made 300 Icelanders slaves) married a Moroccan. Anthony and Grietje were frowned upon before they moved and became large landowners on Long Island.

Evardus early came under the wrath of the incompetent governor and company director van Twiller. Things did not get any better when Twiller was replaced in 1638 by the despotic Willem Kieft , who was widely hated for his arbitrary judgments.

The Indian tribes avenged Kieft’s misdeeds by killing colonists and burning their farms. A few missing pigs were enough for Kieft’s men to murder a number of Indians. It was just as bad for a tribe that sought refuge at New Amsterdam, which was the prelude to a rebellion that nearly wiped out the colony. Peace was made with the tribes in 1645, but the war between Kieft and the righteous Evardus continued.

The walk

Let us follow the Bogardus family on a September Sunday in 1645 as they leave the house on Pearl Street to go to high mass. First comes Anneke with two-year-old Jonas and with newborn Pieter in her arms. Evardus, rosy and round-faced, brings with him Cornelis, who has just turned five, and Annetje, the nine-year-old daughter of Rolf. A few steps behind walk Jan, 9, Sytje 12 and Trijntje who is 16 and of marriageable age.

It is a beautiful autumn day and the family makes their way past the canal where black Angolans have a weekend off from loading the fruit barges. Evardus greets Emanuel van Angola, whom he recently baptized in the church. Older slaves have bought their freedom and become their own farmers not far from Bogardus’s land. Although there are not that many slaves in the colony yet, because the company gets better pay for them in the West Indies.

The walk continues along the weekend-quiet quays. The magistrate’s elders in official uniform and tall hats with silver buckles discuss the week’s issues. Out on the East River, Indians are seen in canoes; are they coming to exchange goods or are they planning to steal from the plantations? Despite the peace, fear remains.

Some colonists lingered in the city where they had taken refuge during the unrest. A number lost their livelihood, even in Jonas Bronck’s Indian-friendly model community in Bronck’s Land (now called the Bronx). The priest’s son from Copenhagen and the Faroe Islands wanted to use money he had received from shipping in Amsterdam to create an Anabaptist model community . Therefore, he filled his ship Brand van Trogen with 35 families who had survived the tidal disaster when 8,000 drowned south of Jutland. In addition to livestock and household goods, this ark also carried a number of books, mostly in Danish, to be read for spiritual edification in ”New York’s first library”.

Anneke exchanges a few Norwegian words with the shipbuilder Dirck Volckertszende Noorman from Bergen who came with Governor General Minuit as early as 1626. He married the beautiful daughter of the Walloon, became the father of the colony’s first born white. He became wealthy in real estate deals, to Swedes in Smith Valley, among other things. Shipyards and builders needed people who could handle pine and therefore Scandinavians were recruited. A dozen different languages are spoken in New Amsterdam and the Nordic ones are among the most common. (Officially 200 Scandinavians came between 1630 and 1674, but there may have been many more).

Outside the director general’s large building, Anneke sees her sister Marritje and her husband, who is Tyman Jansson, who apparently also comes from Marstrand. Tyman is considered the city’s foremost shipbuilder, but now he is marked by the wear and tear on the boats. Therefore, he gets a helping hand from his daughter Elsie (whose husband and son would be hanged for rebellion against the English at the end of the century).

Further up the hill, Sara and Hans Kierstede join with their little son Hans. Hans the elder is the city’s surgeon, having fled here with his brother Joakim after they miraculously survived General Tilly’s mass murder of 30,000 Saxons in Magdeburg.

Sara was only fifteen when she married Hans and many remember the wedding. Evardus had long wanted a new church instead of the old one on top of a mill. After six drinks, the general manager Kieft went around and had the guests sign donations, which then poured in without mercy. So now Evardus can preach in a stone church inside the fort and for seafarers the tower is a reliable landmark.

The tragedy

Many parishioners probably quietly like Evardus’s unsparing sermon where the target is Governor Kieft’s misrule. He responds with cannon fire during high mass and outside the church window a crowd of soldiers shout. In a letter to his homeland, the governor accuses Evardus of drunkenness and dishonesty. The rulers in Holland get tired of the constant quarrels and call the two combatants home for a fight and a trial.

In 1647, Evardus said goodbye to his family to sail to Amsterdam with Kieft on the Princess. But the ship ran aground on the rocks in the Bristol Channel. Perhaps Kieft and Bogardus reconciled before they drowned in the waves. The loss was doubly painful for Anneke, as Sara’s brother-in-law, Joakim Kirstede, also perished. The following year, Anneke’s daughter Annetje died, only twelve years old.

Anneke sells the house on Pearl Street and moves to her two sons Jonas and Pieter in Beverwyck, not far from Laets Burg. There, in her old age, she can sum up a good life for most of her loved ones. There are many of them because, unlike in Bohuslän, not many of the children die.

Sara has ten children and she has worked as an Indian interpreter for the one-legged governor Peter Stuyvesant. Sytje is the widow of a commissioner at Fort Oranje. Willem is the postmaster. Cornelis was a gunsmith before he died. Pieter is on the Beverwyck magistrate’s bench and has negotiated peace with the Indians.

Sister Marritje is, after three marriages, one of the richest people in the colony, perhaps the richest, after her marriage to the real estate worker Govert Loockermans. He sat on the council and did not even crawl for patron in Rensselaerwyck, which became a legal case in Holland. Govert came from Belgium as a poor apprentice cook and earned so well in the fur trade that he was able to buy boats, do business and smuggle like so many others.

Anneke was not a poor woman either. In her will shortly before her death in 1663, she gave one thousand guilders and the property in Manhattan to her first four children. Jonas and Peter got the house in Beverwyck. The heirs were to share the movable property, money, gold and silver items.

When the English took over the colony, the heirs sold the land on the North River to Trinity Church, although there has been some debate about how legitimate it was. Some of Anneke’s approximately one million descendants have, however, unsuccessfully sued for the land, which extends from the former Twin.

/ By Ingemar Lindmark