By Ingemar Lindmark

Kvistrumfortet was Sweden’s Skagerrak lock.

One of the world’s largest nuclear-bomb-proof bunkers should be opened to the public and declared a cultural heritage site—just like in other countries.

In February 2023, Denmark’s North Jutland museums inaugurated the Cold War Museum Regan Vest, located 30 kilometers south of Aalborg. For around 280 SEK, visitors can explore a 600-meter tunnel carved into the limestone. The tour includes a circular excavation with command centers, offices, and accommodations for the royal family, government, and national leadership—totaling 5,500 square meters.

Outside the mountain, a visitor center costing 75 million SEK offers Cold War history exhibits. There’s also a café—if you’re not inclined to spend 250 SEK on a traditional smørrebrød in the fortress canteen.

No More Secrets

The protected bunker in Jutland can even be seen on YouTube. Similar nuclear-proof government bunkers exist across many countries. Some, like Dienstelle Marienthal near Bonn in Germany and the Diefenbunker near Ottawa, Canada, are open to the public.

Britain’s government bunker, Burlington Bunker near Corsham in southwest England, has also been publicly showcased. Unconfirmed sources claim it was prepared during WWII for a Swedish government-in-exile. The Munkedal mountain fortress would have been their last stop before fleeing abroad.

A presidential bunker also exists beneath Camp David in Maryland, likely linked via tunnel to the enormous Pentagon bunker, Raven Rock in Pennsylvania—both visible thanks to President Obama’s transparency initiative Weekend at Camp David, despite these sites still serving a protective role for top military and political leaders.

Military bunkers—both operational and decommissioned—are often featured in the media. A Nordic TV documentary showcased the Holmenkollen installation in Oslo, originally built for the German Luftwaffe and later used by NATO.

Scotland’s Secret Nuclear Command Centre, north of Edinburgh, has been a tourist site since 2014. Presumably, this is where bombers were dispatched, possibly crossing Sweden en route to Soviet targets.

A Fog Over Sweden’s Underground Facilities

In many countries, Cold War history is revisited to foster public preparedness for future crises. But not in Sweden, where secrecy still shrouds defense matters—even after joining NATO.

Recent documentaries by Melker Becker for the Swedish Armed Forces, including If War Comes and When War Comes, and the SVT series Secret Swedish Rooms, offered glimpses into historic military and civil defense sites. However, these were presented only from a tactical or civil defense viewpoint—avoiding the deeper geopolitical context that challenges Sweden’s self-image.

Two former Cold War bunkers are open to the public. The Aeroseum showcases aircraft shelters of the Säve air base on Hisingen, and the Femöre Fortress near Oxelösund offers a coastal artillery experience.

Yet, when it comes to revealing Sweden’s Cold War double game under its so-called neutrality, the lid remains tightly shut. One stark example is the Greger B380 national mountain bunker in Munkedal, 20 km north of Uddevalla.

A Secret of Titanic Proportions

The Greger B380 facility was named after the saint’s day when King Gustaf VI Adolf inaugurated it on March 13, 1958. That year, the Western Naval Command moved in with its staff, operations center, and a forest of antennas on the mountaintop. Bohuslän’s coastal artillery was also directed from this site. The facility could host up to 4,000 people, as revealed to cabinet minister Ulla Lindström—who refused to move in alongside the royal family and other officials.

That statement confirms the bunker’s dual role: military base and national command center. With an estimated 2 million cubic meters of underground space—possibly 500,000 square meters of floor area—it may be among the world’s largest. For comparison, Germany’s Marienthal housed 3,000 people in 83,000 square meters, and Raven Rock could host 5,000 on a similarly sized footprint. Denmark’s Regan Vest and Norway’s Holmenkollen are mere dwarfs at 4,000–5,000 square meters.

Its sheer size alone justifies turning Kvistrumbeutlandrget into a Cold War museum. It was a geopolitical “Kinder Egg” with triple functions:

- Military and naval command

- Intelligence;

- Shelter for the royal family and national leaders;

- Strategic support for oil and supply shipments across the Skagerrak.

Like Opening Tutankhamun’s Tomb

In the early 2000s, contractor Anders Karlsson bought a piece of land south of Kvistrumberget. He dug through soil and concrete to reveal 180 rooms on two floors, once used by the defense’s Radio Älvsborg. Antennas on the mountain enabled communication with naval radio stations and overseas military missions.

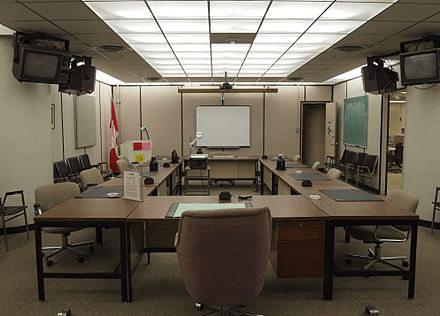

Visitors back then passed armed guards, a blast tunnel, and airtight steel doors before reaching a checkpoint. Even infamous spy Stig Wennerström was stopped at this very point.

Deeper underground lay rooms sealed off with reinforced concrete, forming a vertical “high-rise” within the mountain. At the top were guard barracks. Beneath them were command levels used by the Navy’s Western Command. All entrances are now sealed. Only builders, maintenance workers, or their families can recount what lies within—like reconstructing a puzzle in a spy novel.

Plans in Moscow?

Drawings of Greger B380 might exist in Russian archives. Spy Stig Bergling allegedly photographed piles of defense blueprints from an unlocked cabinet at the Defense Staff Security Department. Though unconfirmed, he is said to have been stationed at Kvistrumberget. He was, at minimum, a reserve officer in the coastal artillery headquartered there.

Whoever breaks through the concrete staircase might find an intact military command center, complete with IBM computers and rows of radar monitors. A retractable antenna atop the mountain fed real-time data into these screens.

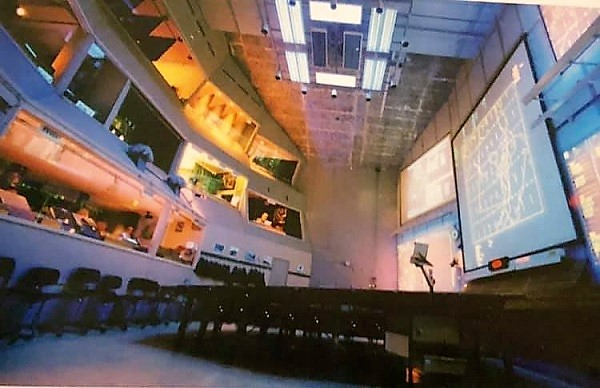

The main command room was nicknamed “The Church.” Operators sat at consoles around the clock, officers watched from balconies, and projections lit up the walls. Some spaces—like the on-site hospital—are rumored to be larger than Uddevalla’s public hospital.

Televerket cables connected the bunker to other command centers. Enemies would be met with advanced systems like the Navy’s STRIKA and Air Force’s STRIL.

A NATO Base?

The sensitive electronics were encased in shock-absorbing springs. A cable technician once overheard voices—Swedish, English, Danish, and Norwegian—from below. Was this a one-time drill, or permanent NATO staffing? Danes living in Munkedal suggest the latter. One of their children still lives there.

Residents saw helicopters land nearby—nationalities were concealed. NATO headquarters in Kolsås (Oslo) and Karup (Denmark) are only about an hour’s flight away.

In the 1970s, eight civilians speaking English crossed the local railway bridge for lunch at a pension. Their American accents raised eyebrows. Were they installing equipment? Were they liaison officers training with Swedes? Similar cross-border drills took place, with Swedes in NATO HQs like Wiesbaden.

One local who delivered Christmas food to the bunker found American officers in uniform celebrating inside—seemingly part of the permanent staff. Their job? Monitoring Eastern threats and coordinating Western responses.

A Complicated Neutrality

“We’ve been militarily non-aligned for 200 years, and it’s served Sweden well,” Prime Minister Magdalena Andersson declared—just two months before applying to NATO. Yet unlike neutrality, non-alignment is not legally defined under the Hague Conventions.

Intelligence scholar Wilhelm Agrell and journalist Mikael Holmström (The Hidden Alliance) have both written about Sweden’s dual-track policy. Was Greger B380 part of this covert alliance? It’s more nuanced than that.

The Kvistrum fortress aimed to keep supply lines open. Oil for three months was stored nearby in places like Hensbacka.

Sweden once invested in a harbor and oil cisterns deep in Norway’s Trondheim fjord—but the plan was abandoned. Norwegians were seen as unreliable, and transport over the mountains was difficult. That left Gothenburg and Bohuslän’s ports as Sweden’s crucial supply and reinforcement points.

Securing these sea lanes required cooperation with Danish and Norwegian militaries. Submarine routes, airspace permissions, and communication infrastructure all had to be coordinated—entirely legal under wartime planning laws.

But did NATO’s reach extend into Kvistrumberget? Were offensive war plans ever drawn up, undermining Sweden’s supposed neutrality? Almost nothing is known for sure. Most agreements were verbal, and any written plans were likely destroyed or locked away. But given the Cold War realities, not coordinating with allies would have been military negligence.